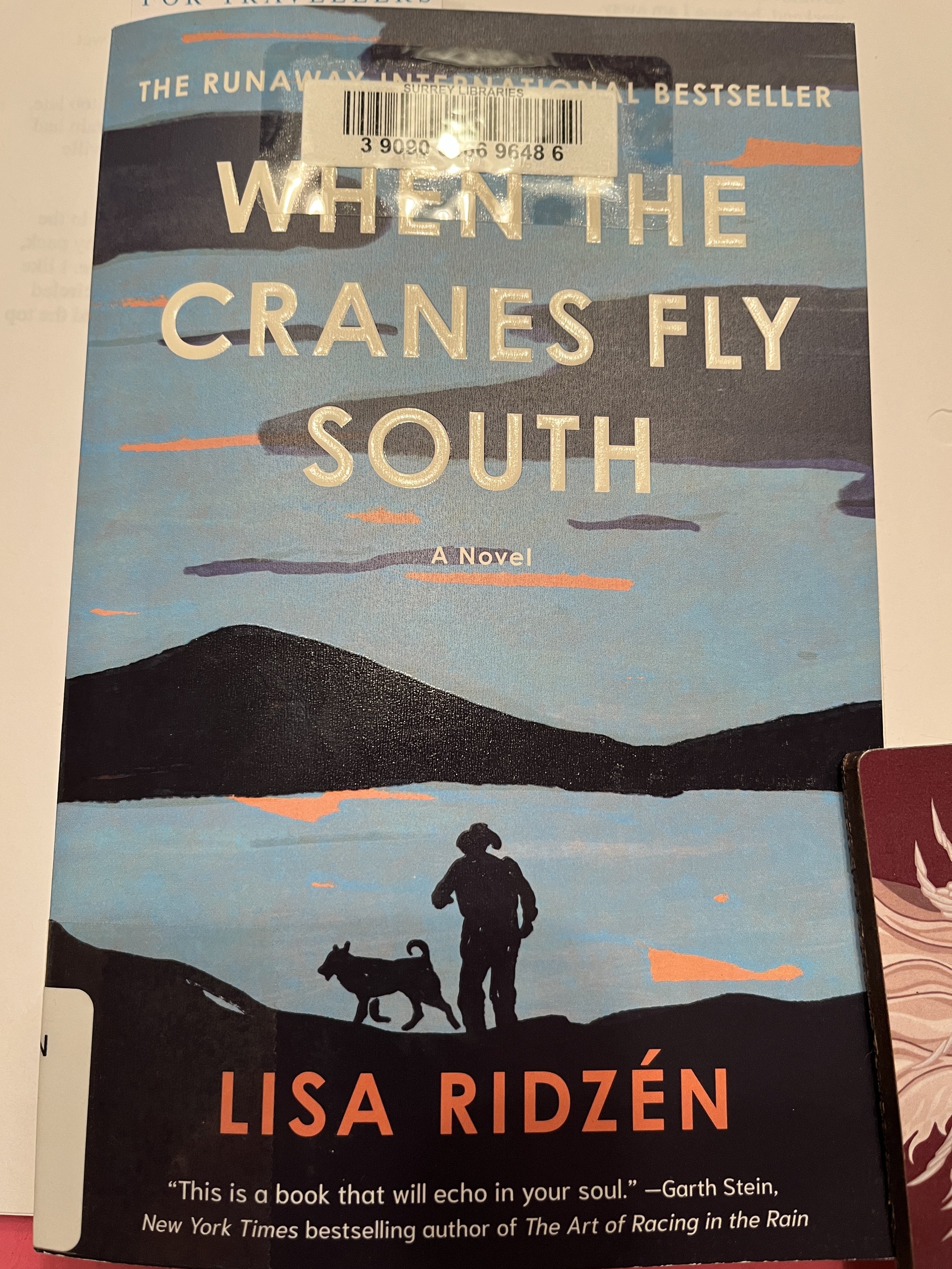

When the Cranes Fly South by Lisa Rizden

On the surface, this simple tale relates a frail old man’s imminent separation from the beloved dog he’s no longer able to care for. From the beginning, the reader knows Bo will have to let Sixten go and will blame his son Hans for relocating the animal.

Through Bo’s thoughts and memories, we are afforded glimpses of eternal themes like parent-child conflict and how society molds us. Bo has been part of passing culture where men took their right to control their women and children for granted. The price was for this “privilege” was self-doubt, emotional isolation, and a crushing sense of responsibility.

Bo has been used to having control over his life, even to the extent of stopping his wife from studying a secretarial course. Defending his male pride as the family provider, he tells her “You shouldn’t have to work.”

Even on the drifting iceberg of loneliness that has left him on the wrong side of the generation gap in an utterly different world, Bo still feels a troubled love for his son and maintains a deep connection with his only granddaughter.

Remembering moments with his family and his best friend Ture, Bo wishes he could have done better. But emotions like blame, rage, guilt and regret are transitory. Along with the rest of humanity, he continues to evolve as he faces hard realities from which there is no escape.

Now that old age and infirmity have robbed him of the control he so prized, he mustlearn to accept that the big decisions about his own life have passed into the hands of his carers and son Hans.

Passing references to contemporary social issues add value to this soulful story. As he becomes aware of the flawed attitudes of his own generation, Bo also questions what is currently considered normal. Why are people constantly working?

Reflecting on “this app nonsense” while his son parks the car, he can’t understand “why there isn’t more of an outcry about the fact that you can’t even park your car without having a mobile phone nowadays.”

Bo’s life in a remote village is backdropped by the beauty of the Swedish countryside that surrounds his home. Riding in his son’s electric car, he looks at Storsjon Lake and remembers how his best friend Ture absolutely believed in the mythic monster reputed to inhabit it. He is still moved by the beauty of Bydallsfjallen, where his granddaughter used to ski. Recently I visited Sweden for the first time, and Bo’s story evoked memories of my late father, a Swedish descendant born to a similar cultural milieu.

As Hans drives his father toward a funeral, Bo remembers how his owh father used to yell at him. “I never stood up to my old man,” he thinks. “That just wasn’t something you did. He was the one who made the decisions…I couldn’t even imagine it any other way.”

To Bo’s way of thinking, “It’s not bloody easy, being human.” Yet his story is ultimately uplifting. Life is mysterious and rich. Undercurrents of love and consolation keep us afloat beneath passing storms of blame and regret, rage and fear. Bo’s final days are rife with challenge but he still manages to find peace.