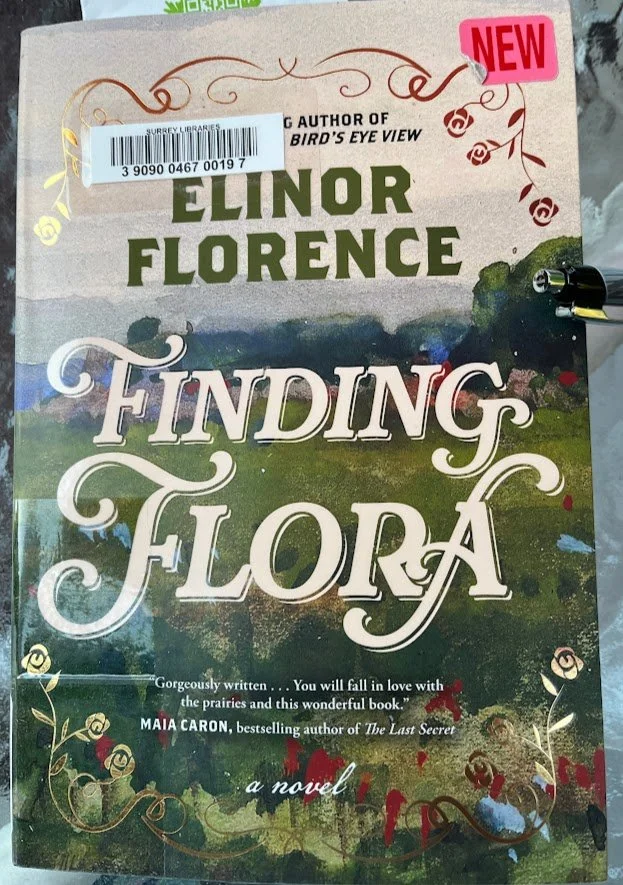

Finding Flora by Elinor Florence

Set in homestead country near Lacombe in the first decade of the twentieth century, this novel portrays a disparate group of women with one goal in common: to have homes of their own. This is an era when women had no vote and no property rights.

Smarting from the social disapprobation that has deprived them of their teaching jobs, the Chicken Ladies have fled the city that deemed their “Boston marriage” beyond the pale to raise poultry In the wilds of rural Alberta. Margaret, the Welsh widow and mother of three has come to Canada to obtain land for herself and her children, risking everything to save her son from working down the coal pit, where his father died.

Newly arrived from Scotland, the naive orphan Flora flees a violent husband by jumping from the train. Horse-breaker Jesse Macdonald, of Scottish and Cree ancestry, is loosely based on Elinor’s grandmother.

Inevitably, troubles of various kind bind the farm women of Ladyville together. After an initial wariness, Jessie and Flora discover they share similar family histories: being removed from their ancestral land—in Flora’s case, as a result of the Scottish clearances.

Born near Edmonton, I spent my first eight years in Alberta. Reading this story aroused delicious memories of the sights, smells and sounds of my prairie childhood. Closing my eyes, I see buffalo beans and black-eyed Susans, stoneboats and wild crocuses. Reading this book evoked the wind in the poplars and the call of the kildeer, along with prairie smells: wild roses and sloughs, fresh shiplap and beer parlours. My mouth waters at the mention of saskatoon pie.

I love learning history by reading fiction, and this book is rife with details I knew nothing about. Though my own grandparents homesteaded in Beaver County, it hadn’t crossed my mind that women would have been allowed to do so a decade before they were allowed to vote.

We meet the very real Irene Parlby, one of the Famous Five who helped women obtain the vote. We also meet a remittance man, and a nurse who served in the Boer War.

Unsurprisingly, the visionary Cornelius Van Horne also puts in an appearance. As he oversees the nation-building project of laying railways, we glimpse his frustration with the land speculators, in particular the now infamous Frank Oliver, who had a neighbourhood in Edmonton named after him. Interestingly, after long discussion, this name was recently changed to a Cree one.

In an time when Canadian society is reflecting on the more dire consequences of colonial projects once taken for granted, kudos to Elinor Florence for taking on the challenge of writing about Alberta’s pioneer days. With heart and verve, she tells a cracking good story reflected against an unvarnished, informative and thought-provoking history of Alberta in the early 20th century.

The book contains many memorable lines. In particular, I empathized with the “pang of sorrow” Flora feels as the plow breaks open the sod “in a black wound,” after “thousands of years of rain and snow and sunshine since the retreat of the glaciers.” A happier moment is her realization, as she looks in the four directions across the prairie, that she is “standing under the same sky that shone on Scotland, on the same earth that houses us all.”

Let me give the last the last word to the country doctor: “‘I love the newness of this country, and the sense of opportunity, the notion that one can change this country and be changed by it.’”