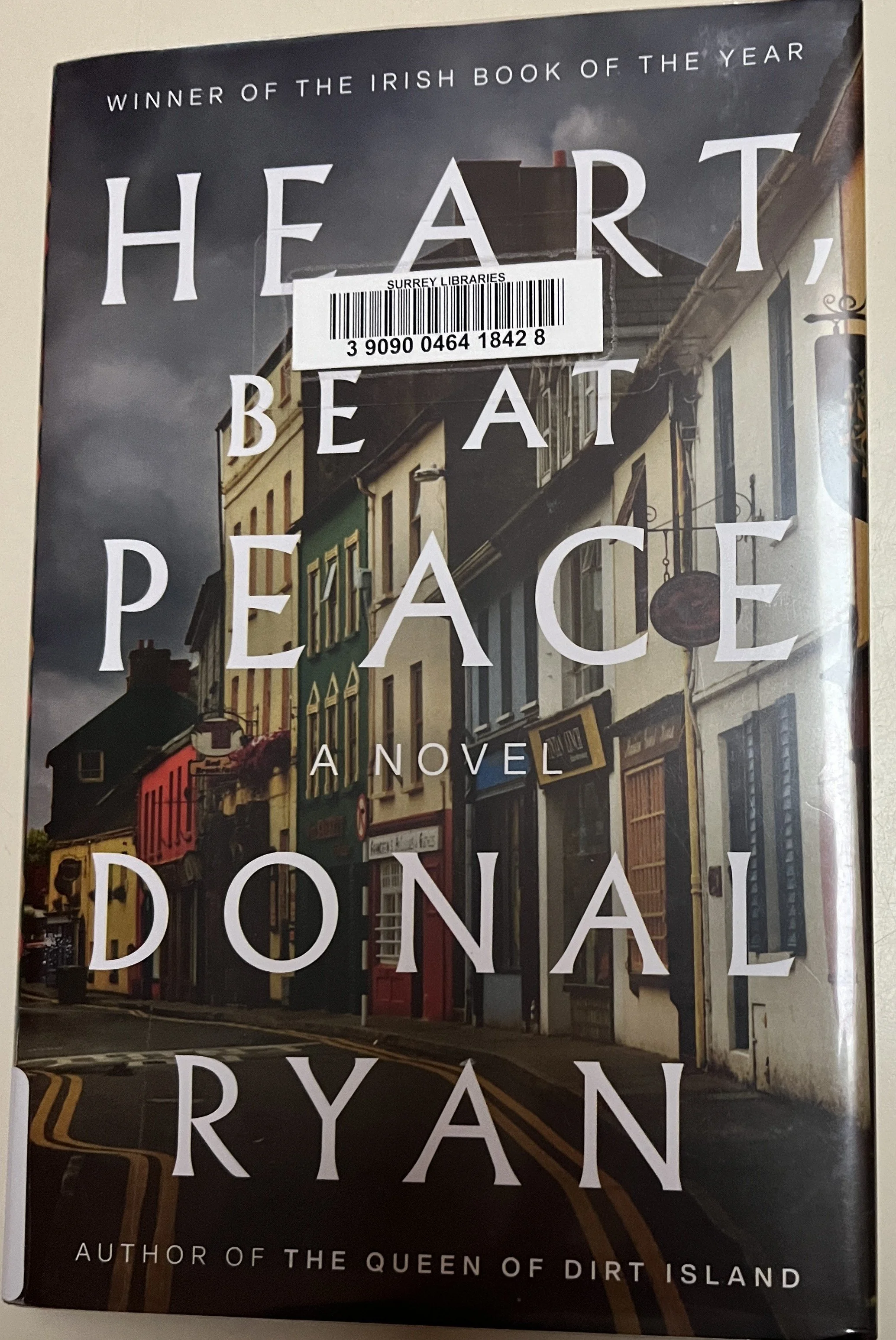

Heart Be At Peace by Donal Ryan

Set in a small town in Ireland, this amazing story is told through the eyes of a huge cast of characters. Inhabitants of the same village, they are connected in various ways to its troubles, past and present. I was drawn in immediately, as much for the stark beauty of Ryan’s language as for the story itself.

First we meet Bobby, now middle-aged, as he notices “I’m way more aware of the things my body is doing.” When he goes on to describe how he decked a violent bully with an elbow to the windpipe, we intuit what’s coming, and when he tells us “I’m not like my father was. I’m not,” we can already feel the violence of his past that makes us sympathize with his struggle to escape the cycle of dysfunction. He thinks he has some secrets from his wife Triona.

His love for her is seen in how sweats in fear of her finding out about his drunken indiscretion. A measure of her love for him is that “even knowing the foolish strut of men among men, the way they have of...reducing the world to a set of basic rules, reverting to their adolescent types,” she forgives him for what to her doesn’t matter. Indeed, Triona knows “what he’s capable of and what’s beyond him;” she knows her husband’s “goodness better than he knows it himself.”

When we meet Josie, he’s recalling what happened when his son Pokey arrived home after a long absence. The father, now a widower, looks at his changed son and feels feels “relief, plain and simple” that the boy is home and safe, and “I could talk to him again, try again to make amends, and get him to make things right somehow for all the people he’d wronged…Before the poor boy even made it as far as the front door I had him forgiven and unforgiven, welcomed and unwelcomed.” Suppressing his rising anger at the son who courted bad trouble and was absent while his mother was dying, Josie imagines he sees “the whirs and clicks in his brain, the gleeful whisper. The auld fella is banjaxed. He’s on the way out. I’ll fall for the house now….I had him judged like that, imagine, before he had even one word spoken.”

We feel Josie’s deep regret for the things he could have done and didn’t do. We feel his poignant memory of his now dead wife, who would make sure the family members were “all okay, even as we were breaking her heart over and over again with all our auld grudges and sourness and silence.”

Defying “the simple equation that has effort on one side and reward on the other,” Pokey gets involved in a fraudulent English language school with a fella living in one of those houses “built on a foundation of bribes and bullshit back in the eighties.” Ruefully, Josie admits he willingly let his son sell him on the idea, which “seemed to make sense.”

Reflecting on his mistakes, the old man recalls how his beloved daughter Mags “had to fight me the hardest, God forgive me. The disgust I felt at having a lesbian for a daughter, the shame of it.” But Josie got past this phase before his dying wife made him promise he’d leave the “door open for Pokey no matter what,” and remind himself every day how much he loved his daughter Maggie.

Descended from Travellers, Lily is a grandmother who describes herself as a witch. On a rare visit to the hospital, which used to be a workhouse, she can sense its former occupants, “feel the cold waves of their suffering washing through time and breaking over me.” In her granddaughter she sees so much of her young self that she “had to come around to living with the fear, that feeling of being overwhelmed by a terrible mixture of love and worry.” In spite of the so-called progress, she reflects “the world is a more dangerous place for a young girl than ever it was before.” Remembering he own teenage years, she knows that time of life is “the shadowy path between childhood and adulthood…[is] pocked and hexed with all sorts of traps and trials.”

Along with the chorus of Irish men and women, we hear the voice of the unemployed foreigner Vasya. Living in his simple camp on the lakeshore, he agrees half-knowingly to ferry illicit cargo across. Recalling his own history, he observes, “Some men can lie with such ease that they quickly begin to believe themselves and so in a way their lies become truth and their sin expunged.” He recalls men he knew, “from Belarus and Armenia and Azerbaijan who changed their nationality with the wind,” sometimes gaining “birth certificates, passports, driving licenses, all sort of legal documents that supported their new realities.” He hears “the ghostly echo” of an old friend “saying things he never said.”

Along with reflecting the lies people tell themselves and others, this story portrays other human strengths and weaknesses. “We never fully leave our childhood,” thinks Josie’s daughter Mags, “we stretch it out along our years and every now and then when we let our grip fail it snaps and reels us back.” After her father’s death, she looks into the doctor’s rheumy eyes as he shakes her hand in condolence. He looks indignant, as though death is “dismantling the world he’d known all his life, gradually evacuating all his certainties, deposing him from the seat of authority he’d occupied with such quiet firmness for so long.”

History and society exert powerful effects on individuals. A case in point is that “according to Mickey, the story of what happened at his house last Sunday had started before Ireland was free.” On the individual level, some lie while others speak truth; some engage in acts that break their communities down, and others help to rebuild them. According to Garda Jim, there are still those who, giving “two fingers to the doubters…[make] a declaration of war on the sad fate so many [are] prepared to accept.” Bobby, he says, “is one of these rare men who measures himself against the well-being of the people around him.”

Jim finds goodness “a hard thing to define,” and “it’s always best to divine…motive” before allow yourself to assess character. “if a person is showy about their good acts,” such acts can be discounted—“If they’re looking for recognition or thanks or some kind of satisfaction or gain outside the simple pleasure of having given of themselves for the good of others, then the merit, for me, is gone.”